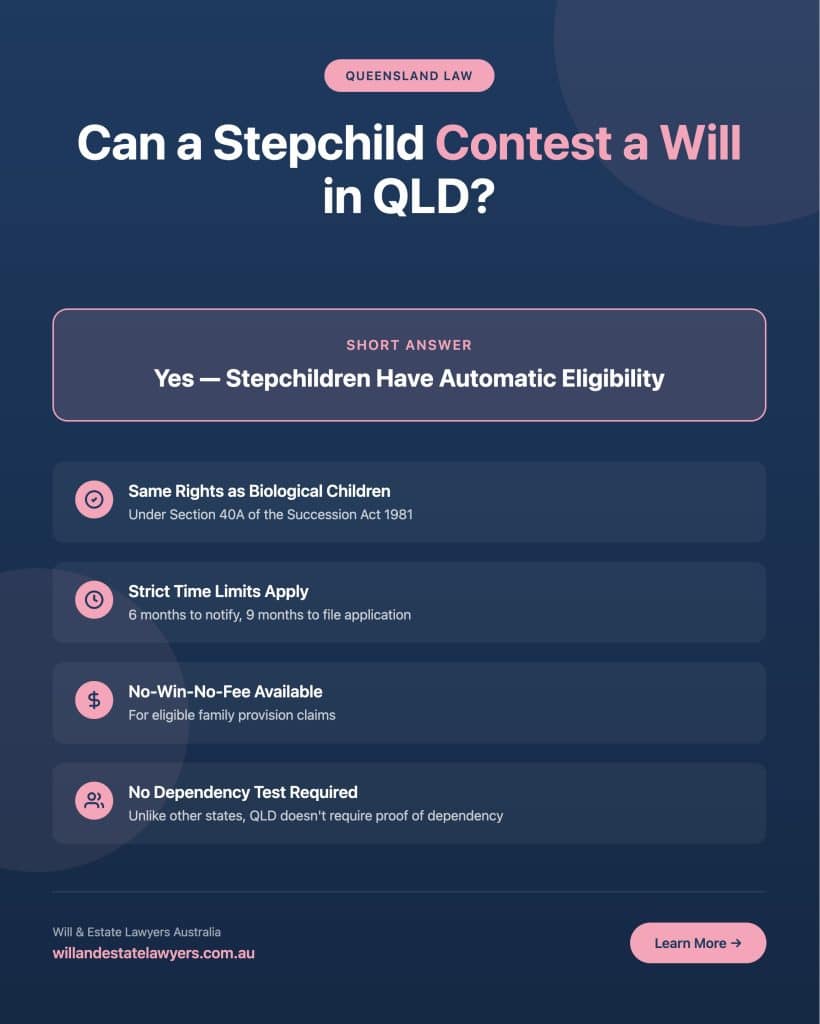

Yes, a stepchild can contest a will in Queensland. Under the Succession Act 1981 (Qld), stepchildren are automatically included in the definition of “child” and have the same rights as biological or adopted children when it comes to contesting a will. This means you don’t need to prove you were “treated as a child of the family” or that you lived with your stepparent—your status as a stepchild is enough to make you eligible.

This is an important distinction because Queensland law treats stepchildren more favourably than some other Australian states. If your stepparent has died and left you little or nothing in their will, you may have grounds to make a family provision application to claim a share of the estate.

However, being eligible to contest a will isn’t the same as winning your claim. The court will consider several factors before deciding whether the will failed to make adequate provision for you. Understanding these factors—and the strict time limits involved—can help you make an informed decision about whether to proceed.

How Queensland Law Defines “Stepchild”

The Succession Act 1981 (Qld) specifically includes stepchildren in its definition of “child” under Section 40A. This automatic inclusion is what makes Queensland’s approach relatively straightforward compared to other jurisdictions.

A stepchild is typically defined as the child of your stepparent’s spouse or de facto partner from a previous relationship. If your biological parent was married to or in a de facto relationship with the deceased person, you qualify as their stepchild under Queensland law.

What this means in practice: You don’t need to demonstrate that your stepparent raised you, financially supported you, or had any particular relationship with you. The legal relationship created through your parent’s marriage or de facto partnership is sufficient to establish your eligibility.

This is particularly relevant for blended families where the stepparent-stepchild relationship varied significantly. Perhaps your stepparent came into your life when you were already an adult, or perhaps you lived with them throughout your childhood. Either way, your eligibility to contest the will remains the same.

It’s worth noting that this automatic inclusion applies regardless of whether your biological parent is still alive or was still in a relationship with the deceased at the time of death. Once the stepchild relationship has been established, it doesn’t dissolve if your parent later divorces the stepparent or passes away.

Stepchildren vs Biological and Adopted Children: Same Rights?

When it comes to eligibility to contest a will, stepchildren have the same rights as biological children and adopted children in Queensland. All three categories fall under the “child” definition in the Succession Act, which means all can make a family provision claim.

However, having the same eligibility doesn’t guarantee the same outcome. The court considers several factors when assessing family provision claims, and the nature of the relationship between the deceased and the applicant is one of them.

Factors the court considers include:

The quality and closeness of the relationship with the deceased person plays a significant role. A stepchild who was raised by their stepparent from a young age may be viewed differently than one who had minimal contact. The court examines the nature and duration of the relationship, any financial support provided, and the deceased’s moral obligations toward the applicant.

The applicant’s financial resources and needs are also critical. The court looks at your current financial position, your ability to support yourself, any disabilities or health conditions, and your age and earning capacity. A stepchild with substantial financial need may have a stronger claim than one who is already financially secure.

The size of the estate matters too. Larger estates are generally more likely to accommodate multiple claims, while smaller estates may mean the court has less flexibility.

Competing claims from other eligible persons can significantly affect outcomes. If a surviving spouse or biological children are also making claims, the court must balance everyone’s needs. A spouse typically receives priority in these situations, which can reduce what’s available for other claimants.

The Family Provision Application Process

If you decide to contest your stepparent’s will, you’ll need to make a family provision application to the District or Supreme Court of Queensland. This isn’t about proving the will is invalid—it’s about demonstrating that the will failed to make adequate provision for your proper maintenance and support.

Step 1: Notify the executor within 6 months

This is a critical deadline that many people miss. You must notify the executor of your intention to make a family provision claim within 6 months of the date of death. This isn’t optional—without this notice, the executor can legally distribute the estate and your claim may become unviable.

The notification doesn’t need to be a formal legal document. A letter stating your intention to make a claim is sufficient, though having a lawyer draft this ensures nothing is missed.

Step 2: File your application within 9 months

Your actual family provision application must be filed in the Supreme Court within 9 months of the date of death. This is a hard deadline, and while extensions are technically possible, the court is reluctant to grant them—especially if the estate has already been distributed.

Step 3: Gather supporting evidence

Your application needs to demonstrate both your eligibility (which, as a stepchild, is straightforward) and why the will’s provision for you was inadequate. This typically includes:

Evidence of your relationship with the deceased, including how long you knew them, the nature of your interactions, and any support they provided. Financial statements showing your current income, assets, debts, and living expenses. Documentation of any health issues, disabilities, or other factors affecting your financial needs. Information about the estate’s assets and the provision made for you (if any) in the will.

Step 4: Mediation and negotiation

Most family provision claims settle before reaching a court hearing. After filing, there’s usually a period of negotiation between the parties, often facilitated by mediation. Early settlement avoids the uncertainty and expense of a trial while still achieving a fair outcome.

Step 5: Court hearing (if needed)

If settlement isn’t possible, the matter proceeds to a hearing where a judge will assess the evidence and decide whether to make an order adjusting the distribution of the estate.

Time Limits: Why Acting Quickly Matters

The time limits for contesting a will in Queensland are strict, and this is where many potential claims fail. There are two key deadlines to understand:

6 months from death: Notice to executor

You must notify the executor in writing of your intention to make a family provision claim within 6 months of the deceased’s death. Without this notice, the executor is entitled to distribute the estate, and once assets have been distributed, your claim becomes much more difficult to pursue.

9 months from death: Court filing

Your family provision application must be filed in the Supreme Court within 9 months of death. Missing this deadline means you’ll need to apply for an extension, which the court may or may not grant.

Can you get an extension?

Extensions are possible but not guaranteed. The court considers factors like why you missed the deadline, whether the estate has been distributed, and whether granting an extension would prejudice other beneficiaries. If the estate has already been fully distributed, an extension may be granted but practically useless—there may be nothing left to claim against.

The message here is clear: if you’re considering challenging a will as a stepchild, seek legal advice as soon as possible. The sooner you act, the more options you’ll have.

What Affects Your Chances of Success?

Being eligible to contest a will doesn’t mean you’ll necessarily receive additional provision from the estate. The court applies a two-stage test established by the High Court in Singer v Berghouse and Vigolo v Bostin:

Stage 1: Did the will fail to make adequate provision for your proper maintenance and support?

Stage 2: If yes, what provision ought the court to order?

Several factors influence how the court answers these questions:

Your relationship with the deceased

While eligibility is automatic for stepchildren, the strength of your claim often depends on the relationship you actually had. Did your stepparent raise you? Did they contribute to your education or support you financially? Did you maintain contact throughout their life? A stepchild who was genuinely part of the family unit typically has a stronger case than one with limited connection.

Your financial circumstances

Courts don’t award additional provision just because you’re eligible—they need to see that you have genuine financial need. Factors include your current income and assets, your debts and financial obligations, your health and ability to work, and any other relevant financial circumstances.

The deceased’s obligations to you

Even if you weren’t close, your stepparent may have had moral obligations toward you that the court recognises. For example, if they made promises about providing for you, or if your biological parent’s relationship with them affected your financial circumstances in some way.

The size of the estate

Larger estates have more capacity to accommodate claims. If the estate is modest and there’s a surviving spouse, the court may find there’s simply not enough to go around.

Competing claims

If others are also contesting the will—including the surviving spouse, biological children, or other stepchildren—the court must balance everyone’s needs against the available assets.

No-Win-No-Fee Options for Stepchildren

One of the barriers to contesting a will is the potential legal costs involved. Court proceedings can be expensive, and many people are understandably reluctant to risk significant legal fees on an uncertain outcome.

That’s why no-win-no-fee arrangements exist for family provision claims. Under these arrangements, you pay no legal fees upfront and only pay if your claim succeeds. This removes much of the financial risk and makes it possible to pursue legitimate claims that might otherwise be abandoned due to cost concerns.

Not every claim qualifies for no-win-no-fee representation. Lawyers typically assess the merits of your case, the size of the estate, and the likelihood of success before offering these arrangements. If your claim is strong and the estate is sufficient, no-win-no-fee may be available.

If you’re considering contesting your stepparent’s will, it’s worth having an initial conversation with a family provision lawyer about whether your circumstances might qualify.

Common Scenarios: When Stepchildren Contest Wills

To give you a sense of when stepchildren typically pursue family provision claims, here are some common scenarios:

Left out entirely: Your stepparent’s will leaves everything to their biological children and nothing to you, despite having raised you alongside them. This complete exclusion may indicate inadequate provision.

Unequal treatment: The will provides $10,000 to you but $200,000 to each biological child. The disparity may not reflect the reality of your relationship with the deceased.

Everything to surviving spouse: The entire estate goes to your stepparent’s surviving partner (who may not be your biological parent), with no provision for any children including you.

Promises not honoured: Your stepparent verbally promised to provide for you, or you relied on expectations that you would inherit, but the will doesn’t reflect this.

Each situation is different, and outcomes depend heavily on the specific facts. What’s important is that being a stepchild doesn’t disqualify you from pursuing a claim—it makes you just as eligible as any other child.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a stepchild contest a will in Queensland?

Yes. Under Section 40A of the Succession Act 1981 (Qld), stepchildren are automatically included in the definition of “child” and can make a family provision application without proving they were dependent on or raised by the deceased.

Are stepchildren entitled to inheritance in Queensland?

Stepchildren have no automatic entitlement to inherit, but they are eligible to contest a will if they believe adequate provision wasn’t made for them. The court decides whether to award additional provision based on the individual circumstances.

Do stepchildren have the same rights as biological children?

In terms of eligibility to contest a will, yes—stepchildren, biological children, and adopted children all fall under the “child” definition. However, the court considers the actual relationship and circumstances when deciding outcomes.

How long do I have to contest my stepparent’s will?

You must notify the executor within 6 months of death and file your application in the Supreme Court within 9 months of death. These deadlines are strict, so seek legal advice promptly.

Next Steps

If you’re a stepchild considering contesting a will in Queensland, time is your biggest constraint. The 6-month notification deadline and 9-month filing deadline mean delays can cost you your opportunity entirely.

Speaking with a family provision lawyer early allows you to understand your options, assess the strength of your claim, and make an informed decision about whether to proceed—all before critical deadlines pass.

For an obligation-free discussion about your circumstances, contact our family provision team on 07 3073 2405.

Disclaimer: This information is general in nature and does not constitute legal advice. For advice specific to your circumstances, please contact us for a consultation.